When British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey famously said on the eve of the Great War that “the lamps are going out all over Europe,” his metaphor struck a chord with generations of Europeans both then and in the ensuing decades. Grey’s words are worth recalling now, as the Old Continent enters the new year more divided and less confident of its future than at any time since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Of course the moment is not as pregnant with tragic foreboding as it was in August 1914, but millions of Europeans share a sense of anxiety about the future. As a French New Year’s card quipped, “May 2022 be not as bad as its predecessor!”

The closing weeks of 2021 were grim on several fronts. Huge protests erupted across Europe at the onset of the second winter of COVID-related restrictions. The protesters focused their anger at the introduction of government COVID “green passes” which prevent the unvaccinated from entering restaurants, museums, public transport, and most shops. Tens of thousands protested from the Netherlands and Belgium to Spain and France, from Germany and Austria to Italy and Croatia, expressing their loss of confidence in their governments and “experts,” a sentiment shared by millions of others who did not join the protests but still refuse to be vaccinated.

The Dutch in particular were incensed by Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s demand that there be “no cuddling the grandkids beneath the Christmas tree.” He subsequently reiterated that “it is absolutely necessary to minimize contact between kids and the elderly.” Such zeal in demonizing a common image of warm family reunion sounded almost sadistically jubilant. It seems that Rutte displayed an important motive in the striving of the elite class to enforce COVID-related restrictions to the point of absurdity: to undermine the traditional family even further.

In addition to the COVID-related angst, the European Union and several countries along its eastern periphery are suffering from an unprecedented energy crisis. The Old Continent is burdened with the highest electricity and natural gas prices ever. It is possible, albeit not yet imminent, that there will be energy shortages and drastically reduced heating to European homes and businesses, especially if the winter proves to be long and cold.

The energy crisis is almost entirely self-inflicted, a reckless gamble that went wrong. The gas buyers—especially in Germany—assumed months ago that they could place limited orders for Russian long-term gas deliveries at favorable prices. Effectively they were betting that those quantities would suffice in combination with renewables and a mild winter, and that they could purchase additional quantities at lower spot market prices if needed. Furthermore, in the midst of an election campaign last summer during which the Greens accused Angela Merkel’s center-right government of being too soft on Putin, political decision-makers apparently decided that they could afford to show Moscow that they were reducing their energy dependence on Russia.

So far everything has gone wrong. One cold wave followed another in the run-up to Christmas. As the experts unafflicted by renewable energy dogma had warned, there was not enough wind to move the turbines—winds were at their weakest for 60 years in 2021—and there was not enough light for the solar panels.

Russia’s state-owned gas exporting giant Gazprom has honored all long-term contracts with buyers in Central and Western Europe so far, and it has pledged to continue doing so. It has not delivered significant additional quantities at higher spot prices, however, and it is by no means obliged to do so. This does not mean that Russia is “weaponizing its energy to blackmail Europe,” as some commentators were quick to conclude. It means that Gazprom is following a finely tuned marketing strategy of selling just as much gas as needed to maintain current, unprecedentedly high spot prices. Its deliveries to Europe will remain stable for the rest of the winter, but there will be no major increases.

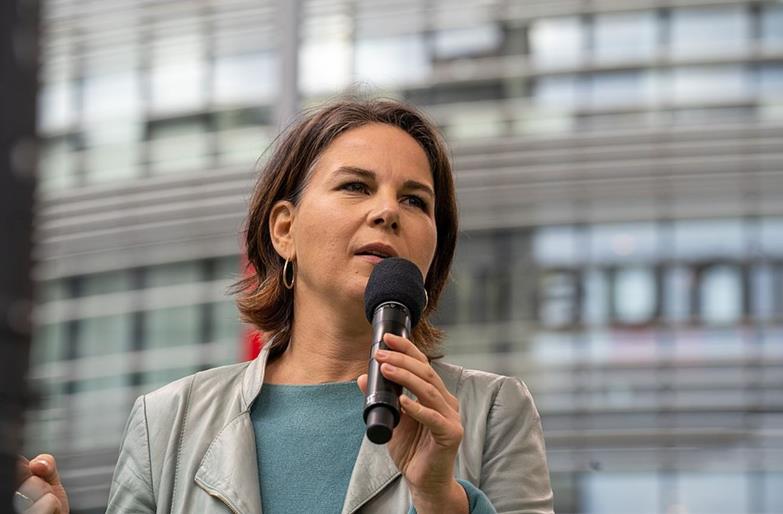

The energy crisis may serve as a necessary reality check for the new German government, which is deeply divided on the country’s long-term energy strategy. Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s “traffic light coalition” (red for the Social Democrats, amber for the pro-business Free Democrats, and green for the Green Party) includes Green Party leader and candidate for Chancellor at last September’s election, Annalena Baerbock, as Germany’s new foreign minister. A leftist crusader in search of a cause, Baerbock has refused to certify the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which was completed last fall, for ideological reasons. The pipeline would bring significant quantities of Russian gas under the Baltic Sea directly to Germany.

Scholz still insists that the issue of certification is purely technical rather than political, and the cold may help him prevail. This would be a welcome development. It is natural for Russia to seek means of energy delivery to Central and Western Europe which would bypass countries that might jeopardize them at a time of tension, notably Ukraine and Poland. It would be equally natural for Germany and other European consumers to diversify their delivery routes. The claim that Nord Stream 2 would increase their dependence on Russian gas is spurious: they will be as much at liberty as before to continue developing alternative sources of energy and to keep looking for alternative suppliers.

To make European energy matters worse, the electric utility giant Électricité de France S.A. (EDF) has announced that it would temporarily shut down up to 30 percent of its nuclear power capacity for long-overdue maintenance until March 2022. This means that France, normally an exporter of power, had to increase imports and use fuel oil for electricity generation.

On the political front, France faces a two-round presidential election on April 10 and 24. The problem of Muslim immigration and the related issue of mostly Sharia-ruled “sensitive urban zones” (Zone urbaine sensible, ZUS) is as acute as ever, but the establishment is likely to prevail yet again with President Emmanuel Macron’s victory in the second round. The position of his most serious challenger, Marine Le Pen—the leader of the National Rally (RN), the successor to the National Front (FN)—has been seriously undermined by the emergence of a new challenger from the right.

Éric Zemmour, routinely described as a “far-right” journalist and TV celebrity, has sparked a media frenzy with his bold, politically incorrect statements about Islam, immigration, and the French identity. Born in 1958 to Jewish parents from Algeria, Zemmour is a prolific writer on history, politics, and culture whose 2014 book, Le Suicide français, sold over half a million copies. He is that rare bird on the French scene, an unabashedly right-leaning intellectual who has managed to stand his ground amidst legions of leftist idiots.

On the last day of November Zemmour declared his candidacy, which is likely to divide the right and may deny Le Pen the second place in the first round. That would mean that Macron would enter the second round certain of victory against a weak leftist opponent. The relentless daily presence of Zemmour in France’s leftist-controlled corporate media may indicate that he is deliberately accorded publicity in order to produce that very outcome.

If conservative French men and women have reason to bewail the inability of the political right to forge a common front, the predicament of their like-minded neighbors across the Rhine is even more disheartening. The new government is even more internationalist-minded than its predecessor, which under Angela Merkel welcomed over a million Middle Eastern “refugees” in 2015. Chancellor Scholz’s Green partners favor a “globalized world” committed to “climate neutrality,” open borders, a “strong Europe” (i.e. further reduction of national sovereignty by the European Union), and even more stringent rules to “fight against racism and xenophobia.”

The old guard of German politics is worried. Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder—a Social Democrat like the new Chancellor—urged the incoming cabinet to soften its foreign policy rhetoric, especially vis-à-vis Russia. But does Olaf Scholz have what it takes to become, like Willy Brandt, a Chancellor who can bring better understanding between West and East, especially between NATO and Russia?

In a Dec. 15 open letter, 27 German ex-diplomats and military officers suggested specific steps for de-escalation and a new beginning in relations with Moscow. “Get out of the escalation spiral!,” urged several senior diplomats and military planners, including Ulrich Brandenburg, the former German ambassador to NATO (2007-2010) and Russia (2010-2013) and retired Brig. Gen. Helmut Ganser, who was department head of military policy at the German NATO mission in Brussels (2004 -2008). Their key message is that “now we need a sober realpolitik.” The experts warn that “Russia sees itself challenged by Western politics” and seeks the preservation of its sphere of influence in the post-Soviet space.

Accepting the notion that spheres of interest are an integral part of any balance-of-power system known to history is unacceptable in Washington, however. The return of global hegemonists to positions of power and influence under the Biden administration means that every spot on the planet is potentially seen as vital to U.S. national security.

Today’s Ukraine came under Russian rule during Empress Catherine the Great’s reign, some years before the U.S. came into being. It became a Soviet republic after the Bolshevik Revolution and stayed that way until 1991. At no time during that roughly two-century period did it occur to any American policy maker that Ukraine’s status relative to Russia was in any way detrimental to the security and well being of the United States.

Russia does not intend to occupy Ukraine, but it does want a neutral buffer zone between its southwestern border and NATO members Poland and Romania. That security concern is both historically understandable and geopolitically justified. Having a Finlandized Ukraine as a bridge between Russia and the EU/NATO, rather than a disputed land, would be a plus-sum-game for all concerned, including up to half of Ukrainian citizens who either speak Russian as their mother tongue or else feel cultural and spiritual kinship with the Russians.

Continuing tensions in Eastern Europe are unnecessary. The Old Continent has enough problems as it is. Like an elegant lady past her prime but still beautiful in an understated, mature way, she needs a stress-free, predictable, and comfortable life. It would be in the American interest for our policy makers to appreciate that need, and to act accordingly.

Germany’s new foreign minister Annalena Baerbock in September 2021.) Flickr-Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Nordrhein-Westfalen, CC BY 2.0