In May of 1996, Lesley Stahl, of 60 Minutes, asked the future Secretary of State Madeleine Albright about the humanitarian disaster in Iraq, which was caused by U.S.-led sanctions. “We have heard that a half a million children have died,” Stahl said. “I mean that’s more children than died in Hiroshima. And—you know, is the price worth it?” Albright, who died on March 23 of this year and who was, at the time of the 60 Minutes interview, President Bill Clinton’s ambassador to the United Nations, replied with barely any hesitation: “I think this is a very hard choice, but the price—we think the price is worth it.”

It is vulgar to deploy reductio ad Hitlerum to villify one’s political and ideological opponents. In the case of Madeleine Albright, however, the National Socialist mindset and temperament are so conspicuous that describing her as “America’s Ribbentrop” is not a term of abuse. It is an empirically justified reference to who she was and what she had done.

We can compare Albright’s 60 Minutes statement to what we find in the notorious Posen speech, by SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, given to an inner group of Nazi leaders on Oct. 4, 1943. He used a different order of magnitude when referring to the victims to make his point, but that point itself was pure Albright:

What happens to the Russians, what happens to the Czechs, is a matter of utter indifference to me. … Whether the other races live in comfort or perish of hunger interests me only in so far as we need them as slaves for our culture; … Whether or not 10,000 Russian women collapse from exhaustion while digging a tank ditch interests me only in so far as the tank ditch is completed for Germany.

Albright’s statement about the death of half a million children being the price worth paying for a set of discrete foreign policy objectives would have been unimaginable for a senior official in any civilized country before the Old World was brutalized, first by Bolshevism and then by Nazism.

Even after World War II, it would have been impossible for the civilized men of stature who shaped the U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War—from George C. Marshall, George Kennan and Dean Acheson, to Cyrus Vance, James Baker, and Lawrence Eagleburger—to make a statement of this kind. Unlike Albright, these gentlemen (and many others of their ilk and breeding in positions of power) were true Americans and therefore would have considered it very poor form to declare, as Albright did in February 1998 on the Today Show that America is inherently superior to the rest of the world:

If we have to use force, it is because we are America; we are the indispensable nation. We stand tall and we see further than other countries into the future, and we see the danger here to all of us.

Albright had no qualms about making such statements, however. For her, “America” was merely a tool of her will to power, a virtual entity to be remade in the image of anarcho-tyrannical national socialism at home and internationalist imperialism abroad. “What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?” she once screamed at Colin Powell.

Albright was not “patriotic” in any conventional sense of the term and never had anything in common with the real and historic America. She saw the United States merely as the host organism for the exercise of her oversized ego and her ideological obsessions. Like her successor Hillary Clinton, who came to Foggy Bottom a decade after her, and like the collective in control of “President Biden” today, Albright saw the need for America to be a hyper-state in order to be an effective, if violent, global hegemon. Her triumphalist megalomania was light years away from a patriotic appreciation of one’s nation, either by birth or by adoption.

A psychotic quest for power and dominance was Albright’s driving force, and the exceptionalist discourse its justification. In this aggressive demeanor, she was remarkably similar to the late Sen. John McCain. Neither had ever seen a foreign war they did not like. In global affairs, McCain’s “vision” amounted to assailing designated adversaries—anyone, that is, unenthusiastic about America’s monopolar global empire—and demanding they be forced into submission by bombs and boots on the ground. Both supported the U.S.-led NATO intervention against the Serbs and on the side of the Muslims in Bosnia 1993-1995, which the late Sir Alfred Sherman described as “America’s own war,” while bewailing “that the White House has chosen a Secretary of State who is a Cold War junkie, a connoisseur of confrontation, a woman living too passionately in the past, eager to seize the first opportunity to show how the old battles should have been fought, how the West should have Won at Munich.”

For years after the peace agreement at Dayton ended the Bosnian conflict, both Albright and McCain passionately wanted Bill Clinton’s war of aggression against Serbia in March 1999 to go ahead. Her role in engineering that war was even more sinister and effective than McCain’s. To that end she deliberately, mendaciously, presented the Serbs at the Château de Rambouillet conference near Paris in February 1999 with not one but two impossible demands, neither of which was subject to prior authorization by the UN Security Council or by America’s allies:

- Belgrade must agree to a referendum on independence in the province of Kosovo within three years (the outcome of which would have been a foregone conclusion); and

- Belgrade must accept the right of NATO troops to move through Serbia under arms as they deem fit “to access Kosovo,” and enjoy exterritorial immunity to boot.

Serbia was bombed for 78 days, starting on 24 March 1999, not “to save the Albanians from genocide” as falsely claimed in its aftermath, but because Belgrade refused to accept Albright’s ultimatum. No sovereign country could accept it. Of course Albright was triumphant. Her aides were giving each other high-fives because the post was set too high for the Serbs to jump.

The comparison to Munich Agreement of 1938, which allowed Germany to make impossible demands of Czechoslovakia, is obvious, but there is a difference. The Clinton administration, on Albright’s insistence, decided that there would have to be war no matter what. Its major underlying purpose was to reassert American hegemony over Western Europe by getting the Europeans to agree to the use of force on Washington’s orders. Her disastrous war against Serbia took a shocking human, ecological and artistic cost. As our editor Paul Gottfried has noted, the globalist-liberal establishment to which Albright belonged treated Kosovo exactly the way they handled South Africa. They took the anti-white anti-Christian side in each case and then acted as enablers for the “oppressed” group as it proceeded to murder or expel the Christians or white Christians.

Like Ribbentrop and others tried at Nuremberg, Madeleine Albright was guilty of crimes against peace, of planning a war of aggression, and advocating war crimes. Predictably she was spared critical scrutiny by the commentariat and approved intelligentsia. Both America and the world would have been better places if she had never existed.

(The original version of this article was updated with more detail in the fourth, eighth, ninth, eleventh, and concluding paragraphs, and a sentence from the conclusion was moved up to the second paragraph.)

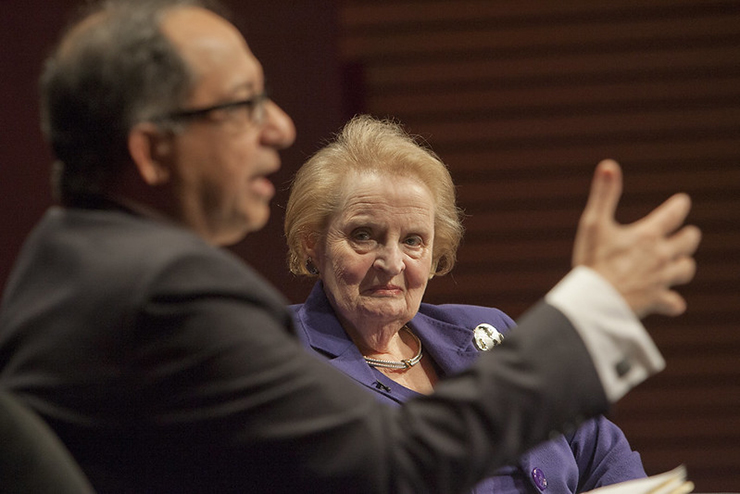

Former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright speaks with World Bank Group Senior Vice President and Chief Economist Kaushik Basu at a 2014 conference (Simone D. McCourtie / World Bank via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)