Addressing a Boston anti-slavery audience in 1865, abolitionist Frederick Douglass asked, “What shall we do with the Negro?” The answer he provided was a favorite of the conservative economist Walter E. Williams, though if Douglass were to utter it today he would probably be condemned by Black Lives Matter and deplatformed from social media:

Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are worm-eaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall!

Douglass was a great advocate of “self-made men,” and was willing to place the destiny of the freedmen in their own hands. So, it is not surprising that Walter Williams was fond of quoting Douglass on this theme. Both men believed that genuine liberty must mean not only the liberty to strive and succeed, but the liberty to fail, too.

Williams, who died in December 2020, deeply valued the whole spectrum of American freedoms, but his perennial concern was economic liberty. For 40 years, in a number of scholarly works and hundreds of syndicated columns, Williams was an unflagging critic of government interference in American lives. He is often known as a libertarian, but in the second half of his career, he increasingly allied himself with paleoconservatives on social and cultural issues—an association that occasionally exposed unresolved tensions in his work.

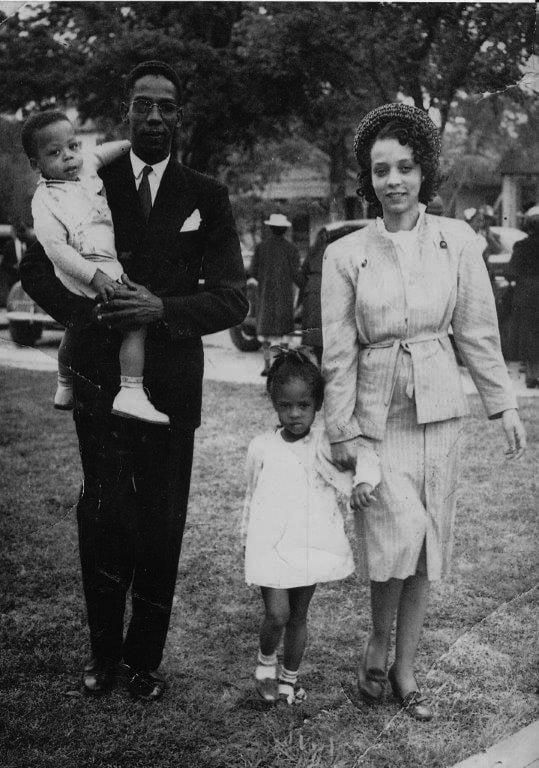

Image: Walter E. Williams as a child, photographed with his father, mother, and sister (Walter Williams / via Twitter)

Born in Philadelphia in 1936, Williams was himself a self-made man, yet in reading his autobiography, Up from the Projects (2010), one recognizes the powerful influence of his mother, Catherine. She single-handedly kept Williams and his sister out of serious poverty after their father abandoned the family not long after Williams’ birth. In 1941 Catherine moved her family to the Richard Allen Homes, a housing project in North Philadelphia, which Williams described as a black “lower middle-class” neighborhood. The Richard Allen project was a very different sort of place than the slums that would emerge in minority neighborhoods in many American cities after the 1960s. There was little serious crime; gangs and unwed mothers were rare; and teenage unemployment rates were lower on average than in many white communities.

Williams laments the fact that children growing up in North Philly today, attending “rotten” schools and dwelling in fatherless homes, have greatly diminished opportunities to work. Such opportunities, he writes, “not only provide the pride and self-confidence that comes from financial semi-independence,” but also teach young people how to achieve success in their adult years.

After high school, Williams drifted back and forth between Philadelphia and Los Angeles—where his father had settled and remarried—making two abortive attempts to start college. Eventually settling on Philadelphia, he drifted from one job to another. This rudderless period in his life found its nadir when he was charged in 1958 by the Philadelphia police for resisting arrest and assaulting an officer. The assault charges were false, by Williams’ account, though he was found guilty and given a lenient sentence. The bright spot in that year was that he was introduced to his future wife and lifelong companion, Connie Taylor, who would prove to be the rudder he needed.

In 1959 Williams began two years of service in the Army, about which he was fond of saying that serving in the military is a “million-dollar experience that you wouldn’t do again for a million dollars.” His rebellious tendencies were very much on display during this period, especially after discovering that segregation among the ranks was still the reality, despite the Army’s claims to the contrary. Blacks, by his observation, were rarely promoted into administrative positions but were usually relegated to maintenance jobs.

Until the day he was discharged in 1961, Williams made it his business to disrupt the racial status quo, usually by way of pranks. In one instance at Fort Stewart, where he had been assigned to the motor pool, he was ordered by his sergeant to paint a two-and-a-half-ton truck. “The whole thing?” he asked, playing the role of a half-wit. “Yes!” said the sergeant. So Williams proceeded to paint every inch of the truck, including the windshield, the windows, and the tires. Naturally, he was transferred out of the motor pool, as had been his intent.

After his Army stint, Williams returned to school and finished his bachelor’s degree in economics at California State College in 1965, then entered graduate school at UCLA. He was at that time an admirer of Malcolm X and an LBJ liberal, voting against Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election. Yet he was also attracted by libertarianism and began to read widely among great libertarian thinkers like Frédéric Bastiat and Friedrich Hayek. Among the professors who influenced Williams was Thomas Sowell, an economist who would thereafter become a lifelong friend and collaborator.

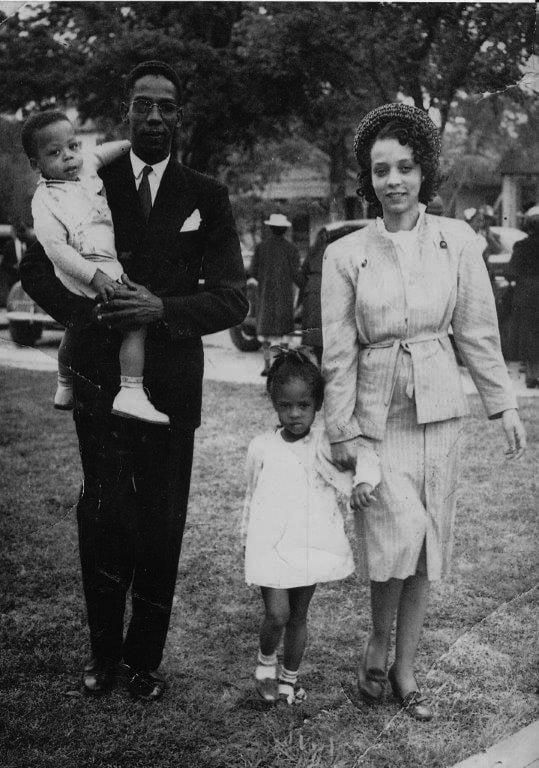

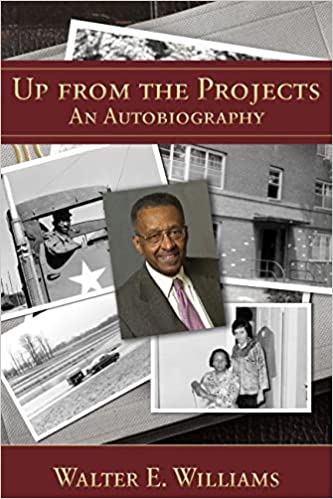

In 1972 Williams was hired as the director of the Urban Institute, in Washington D.C., where he completed his dissertation and began the research that would result 10 years later in The State Against Blacks (1982), in which he painstakingly examined the many ways that government stifles the economic activity of minorities, oftentimes despite good intentions to the contrary.

One example is minimum wage laws, a form of “economic malpractice” that he railed against frequently over the years. Although study after study confirms that minimum wage mandates contribute directly to rising rates of unemployment among poor and unskilled workers, some prominent economists routinely call for minimum wage hikes. However, as Williams wrote, employers themselves recognize that the cost of employing low-skilled workers is greater than the return those workers bring to their businesses. So they look for ways to eliminate the need for such workers, through automation, for instance. Moreover, the oft-made claim that minimum wage laws combat poverty is ludicrous. Prominent economists who make such claims do so not out of ignorance, Williams asserted, but to ensure that their “compassionate” stance will secure them a place on the “brie, tofu and champagne circuit.”

Many of the arguments in The State Against Blacks are reprised in Williams’ 2011 book, Race & Economics: How Much Can Be Blamed on Discrimination? But this later work is a more sweeping indictment of the regulatory state, and it reflects the debates that followed the Great Recession of 2007-2009. What motivated the banks to engage in reckless subprime lending? Williams argued that although there is no single answer to that question, for years the banks had been accused of systematic mortgage discrimination against blacks and other minorities. Already in 1977, with the passage of the Community Reinvestment Act, and then via a host of further legislative initiatives in the 1990s, lenders found themselves under constant surveillance by the Federal Reserve Banks, which had become, in effect, instruments of egalitarian redistribution.

In a 2009 review of Sowell’s The Housing Boom and Bust, Williams emphasized that such initiatives were not just a Democrat hobby horse but were also pushed by the Bush administration, which pressured Congress to enact legislation requiring the Federal Housing Administration to “make zero-down-payment loans at low-interest rates to low-income Americans.” In his review, Williams pointed out that during the last years of the Bush presidency, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had accumulated roughly $1 trillion in subprime loans and had guaranteed at least twice that much in mortgages.

Promoters of all this risky lending, such as Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.), later blamed the crisis on a lack of sufficient regulation in the private sector. Williams disposed of this claim easily: Between 1980 and 2007, “regulatory spending … almost tripled, rising from $725 million to $2.07 billion.”

For years, both Williams and Sowell had been among those crying out against the recklessness of subprime lending, to no avail. Their essential argument was simply that government interference in the free market economy, at any level, can only lead to economic loss for everyone concerned—except, of course, the politicians and bureaucrats who feast on the fatted calf of regulatory spending.

By 1974 Williams began teaching at Temple University, a stint that lasted six years, though it was interrupted by a year-long fellowship at the Hoover Institution. In 1980 Williams joined the Economics faculty at George Mason University, where he would remain for the rest of his teaching career. Among his scholarly endeavors in the 1980s was the book, South Africa’s War Against Capitalism (1989), which challenges the standard view that the apartheid system was driven fundamentally by racism. While he did not deny that racism was a major factor in the regime, he demonstrated that apartheid was maintained in practice only by extensive government interference in the market, forcing employers in many sectors of the South African economy to submit to “whites only” hiring practices even when they went against their economic interests.

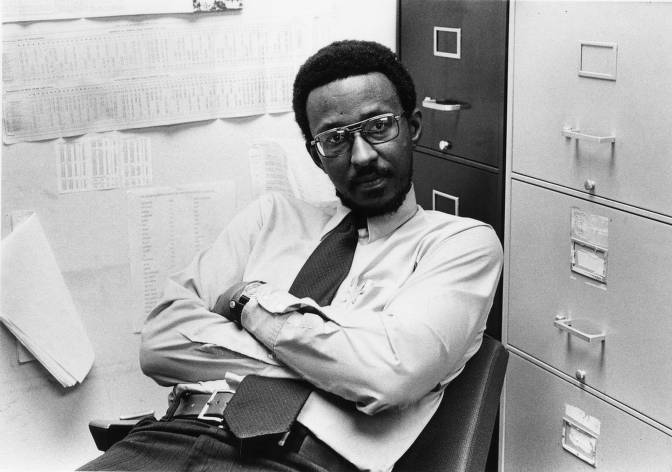

Image: Walter E. Williams as a professor at Temple University (Temple University)

In the late 1970s, Williams began writing a weekly newspaper column for the Philadelphia Tribune, then in 1980 for the Richmond Times-Dispatch. By 1991 he joined the Creators Syndicate, which began publishing his columns nationwide, allowing him eventually to reach an enormous audience in over 140 newspapers and magazines. In fact, most of his American readers first encountered Williams’ ideas through his columns, many of which were also republished in his books, beginning with America: A Minority Viewpoint (1982) and concluding with American Contempt for Liberty (2015).

In his weekly columns reflecting on current events, often humorous and always pithy, he ranged well beyond economics and race to explore education, democracy, the cult of rights, even health and environmental controversies—just to name a few. While the demands of these weekly columns regrettably brought an end to his more scholarly work, it is also true that their popularity made him a powerful force in shaping American opinion for the better—that is, in a more conservative direction.

But to what extent do the views of the libertarian Williams align with those of more traditionally minded conservatives? The answer is that, especially in the last 25 years of his writing life, most of his positions were reliably conservative. Indeed, at times, he sounded like a man of the Old Right in his defense of the Tenth Amendment and state sovereignty or in his provocative stance on nullification. In a 2009 column, “Parting Company,” he quoted a number of state ratification documents between 1788 and 1790 to show that the people believed that the Union was a creation of the states and that those states had every right to nullify unconstitutional laws passed at the federal level. He acknowledged that most Americans today “say to hell with the Tenth Amendment limits on the federal government.” But what, he asked, might be a “more peaceful solution” to an irresolvable conflict between state and federal powers? “[O]ne group of Americans seeking to impose their vision on others or simply parting company?”

In one of the last columns he penned, “Historical Ignorance and Confederate Generals” (July 2020), Williams eloquently refuted the claims of Gen. Mark Milley that the secession of the Confederate states was an act of “treason.” Perhaps it was Williams’ steadfast refusal over the years to demonize the South and her military heroes that led the editors of Southern Partisan to memorialize his death by publishing a eulogy penned by his old ally, Sowell.

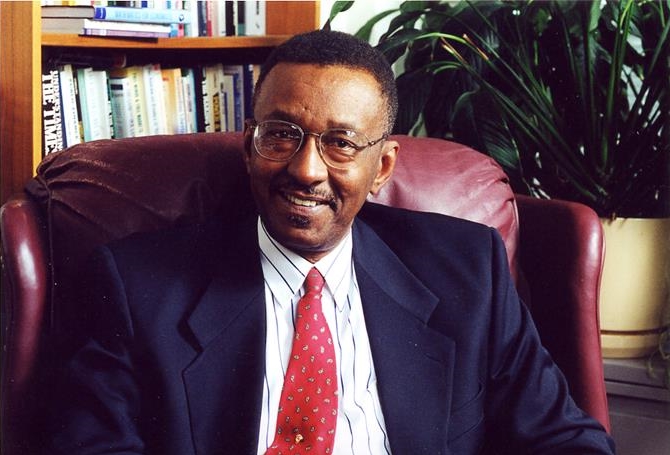

Image: Walter E. Williams (Creators Syndicate)

On the other hand, Williams’ libertarianism is sometimes uncomfortably extreme, veering at moments toward an atomistic, neo-Lockean notion of the individual as an entity undetermined by social bonds. This is perhaps best illustrated by his position on whether one has the right to sell one’s organs on the open market. In a 1999 interview with the Independent Institute, and then in a 2002 column, “My Organs Are for Sale,” he argued that the controversy is essentially a question of ownership. The body, he said, is one’s private property. If people can sell their used cars or their refrigerators, why not their body parts?

In the U.S., the sale of bodily organs—by the “owner” or by anyone else—was then and is still illegal. One can donate but not traffic in hearts or livers. The problem, said Williams, is a matter of market scarcity. Donors are too few, and demand is high. By the rational calculus of the free market, the solution is to create incentive for individuals (or their families) to profit by the sale of their organs. If on your deathbed, the argument goes, you instruct a family member to sell your still-functioning organs (after all, it would be a waste to consign them to the tomb) and reap a healthy monetary gain, then you are doing a good deed for your family as well as benefiting society. If someone objects that to do so would be to desecrate your body by reducing its parts to commodities, that would be mere sentiment.

Needless to say, many conservatives, especially those adhering to traditional religious faiths, would reject such a rational calculus. Even if in some limited sense my body is my property, it is certainly not the same sort of property as my automobile. The body, even after death, is not merely an object; it is also a “subject”—that is, the repository of my soul (to put it in religious terms) or the locus of my will, my imagination, and my familial associations. The Western tradition, dating back at least as far as the Iliad, testifies to this deep-seated intuition. After Achilles repeatedly desecrates the body of the fallen Hector, he is finally brought to his senses and shamed by Priam, Hector’s grieving old father, who reminds Achilles of his own dear father. Thus Achilles relents and allows a proper burial.

While Williams admired Frederick Douglass, he was in many ways closer in spirit to the great libertarian novelist and essayist Zora Neale Hurston. He never cited her work, though both he and Hurston were honored in a round table discussion in 2021 on “Race and Liberty in America,” hosted by the Independent Institute, a libertarian think tank. Like Hurston, Williams was an unflagging proponent of individual liberty as well as a trenchant critic of black leaders who robbed African Americans of the spirit of independence by fostering in them a culture of resentment against white oppression.

Hurston, in a brief auto-biographical essay, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” vigorously rejected what she famously called the “sobbing school of negrohood”—that is, the school of victimology championed by the likes of W.E.B. DuBois. She believed that the philosophy of “racial pride” peddled by the Harlem “Nigeratti” was little more than a form of tribalism that allowed blacks to evade any responsibility for their own failures. While Williams, like Hurston, never denied the historical reality of discrimination against blacks, he never succumbed to the temptation to don the robes of the perpetually aggrieved.

Walter E. Williams (portrait photo courtesy of Creators Syndicate)

Leave a Reply