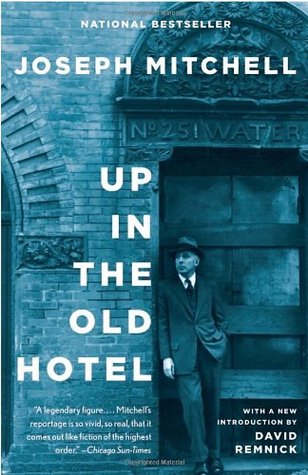

Long regarded by critics, fans, and various of his colleagues at the New Yorker as America’s finest literary journalist, 85-year-old Joseph Mitchell had not, until recently, published a word since 1965, and people wondered what he was doing in his small cubicle at the New Yorker‘s offices, where he has regularly appeared for over half a century. The answer, in part, is that Mitchell was collecting and editing old work and writing new work for his latest book Up in the Old Hotel, a 718-page collection of his best writing that includes four long out-of-print books: McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon, Old Mr. Flood, The Bottom of the Harbor, and Joe Gould’s Secret.

Born and raised in the small town of Fairmont, North Carolina, Mitchell attended the University of North Carolina for four years but did not graduate. In 1929 (at age 21) he arrived in New York seeking a job in journalism. He found work at several newspapers—first at the New York World and in later years at the Herald Tribune and the World Telegram—as a night-beat reporter, a job that inspired in him a lifelong fascination for the raffish side of urban life. During his years as a newspaper reporter (from 1929 to 1938, the year he joined the staff of the New Yorker), Mitchell was happiest interviewing and writing about “unusual” characters—preachers and minor league gangsters, “obsessives, imposters, fanatics, and lost souls.”

He wrote about the black gangster Gilligan Holton, owner of Harlem nightspots with names like Busted and the Broken Leg. He wrote about street preachers like the Reverend James Jefferson Davis Hall, who carried a Where Will You Spend Eternity? sign up and down the sidewalks of the theater district. He wrote about Miss Mazie Gordon, owner of the Venice, a movie theater in the Bowery. A tough-talking, chain-smoking, peroxide blonde secular saint, Mazie sold tickets from 9:30 A.M. until 11 P.M. seven days a week and spent the last three hours of her day—from 11 P.M. to 2 A.M.—touring the Bowery, handing out money to the down and out, getting drunks to flophouses on cold nights, and calling ambulances for the injured. (Mitchell, always a meticulous researcher, found that Mazie had called more ambulances than any private citizen in New York.) He wrote about New York saloons like McSorley’s and Dick’s Bar and Grill—and about their owners. Before locking up for the night, John McSorley, well into his 80’s, would grill himself a three-pound sirloin steak and consume hollowed-out loaves of French bread stuffed with whole onions. He wrote about Captain Charley’s Museum for Intelligent People. He wrote about a man who sold “racing cockroaches to society people.” He wrote about Billy Sunday, about Tammany Hall politicians, about lady boxers; about fishermen, tugboat captains, and butchers; about urban gypsies, bearded ladies, fan dancers, pickpockets, Mohawk Indians, and child geniuses.

But it was not until Mitchell became a staff writer for the New Yorker that he was able to produce the work, the long “fact pieces” and portraits, that established his reputation as reporter and artist par excellence—as, to quote critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, “the paragon of reporters.” The New Yorker freed Mitchell from the pressures of the daily newspaper deadline, and even though he continued to write about many of the same people and places he had described as a newspaper reporter, as a New Yorker writer he had the time and freedom to develop these people and places in much greater depth and detail, so that what were originally sketches became richly detailed, enduring portraits.

Like “Mazie,” Mitchell’s “I’he Old House at Home”—the first of the 27 pieces that make up his book McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon—was originally a newspaper sketch, and as such it is a highly entertaining, vivid description of a venerable New York institution founded in 1854 and largely unchanged in the 1940’s, when Mitchell started writing about it. In the early 1940’s, as m 1854, the floors of McSorley’s are sawdust-covered. A potbellied stove provides warmth. There is no cash register— change is made from a wooden box. Only ale is served—no whiskey, much less wine or liqueurs. There is a free lunch consisting of crackers, sliced onions, and hunks of cheddar cheese. Women are banned (though a woman owned the place in the 1940’s). Four of five customers are Irish workingmen (brick layers, dock workers, truck drivers) or ancient Irish retirees drinking up their pension checks. John McSorley’s 1854 sign—”Be Good or Be Gone”—is still prominently displayed.

Mitchell’s New York, of course, is long gone. He writes, to use John Cheever’s description, of a time when “the city of New York was still filled with a river of light, when you heard the Benny Goodman quartets from a radio in the corner stationery store, and when almost everybody wore a hat.” The New York of the 30’s, 40’s, and early 50’s was a gentler, kinder, incomparably safer city, wherein at 2:00 in the morning one could walk unafraid in tough neighborhoods—”in the slums,” as E.B. White wrote in his classic essay “Here Is New York,” amidst “poverty and bad housing . . . in the reassuring safety of family life.” Mitchell’s New York is really the New York of “usual” people, of working- and middle-class people, of family people, of people living by traditional values, of decent people who, though they may be creatures of immoderation, self-declared atheists cynical and comically irreverent about traditional values, lead essentially religious lives in the knowledge, conscious or unconscious, that the sanity, stability, and safety of their world depends on those values.

Mitchell quit writing in the early 60’s because, he says, “the city changed on me.” One need not be highly imaginative to know what he means.

[Up in the Old Hotel: And Other Stories, by Joseph Mitchell (New York: Pantheon) 718pp., $27.50]

Leave a Reply