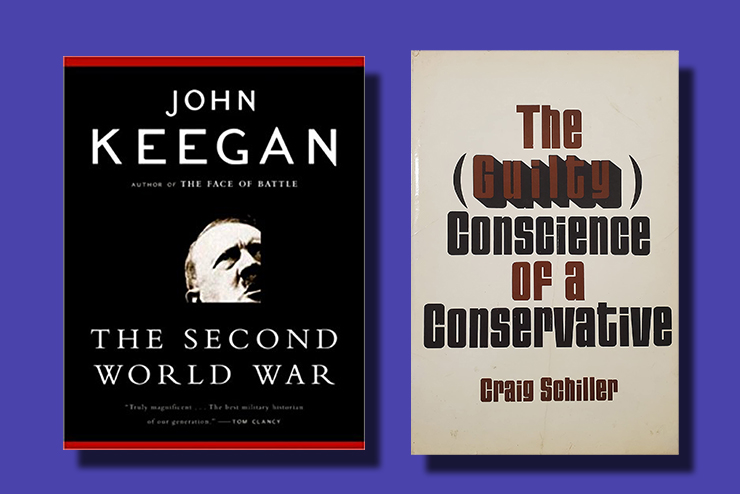

This history of World War II should occupy an eminent position in any collection of studies on that conflict; it is a comprehensive treatment of its subject that stands head-and-shoulders above most of the stream of books issued since its publication in 1989. I reread it recently and have consulted it frequently.

For many years, John Keegan (19342012) was a senior military lecturer at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. In 1986 he became the defense correspondent of The Daily Telegraph. The 607 pages of this book cannot disappoint readers familiar with his other books of military history, including The Face of Battle (1976) and The Price of Admiralty (1988).

Notice the title: clear, simple; nothing misleading; no fancy words or branding. It can be contrasted to that of a Yale University Press volume, The Arts of Intimacy (2009). What might you suppose that title means? It reveals nothing about the topic; the subtitle is necessary: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castilian Culture. Such slanting and willed obfuscation are all too common. Keegan’s straightforward title mirrors his study. No implications, no branding; “just the facts.”

The study is organized chronologically in six parts, by periods and theatres, starting with “The War in the West, 193943” and concluding with “The War in the Pacific, 1943-45.” For each phase, there is an identical, though flexible, topical approach that includes sections on narrative, strategic analysis, battle piece, and “theme of war.” As this organizational pattern suggests, Keegan’s text is reflective, not merely reportorial. Eschewing modish ideological and subjective responses, he nevertheless provides assessments. He is, moreover, a good stylist; his writing is both lucid and searching. With respect to illustrations, the volume lies halfway between, say, 2194 Days of War: An Illustrated Chronology of the Second World War—a hefty 1977 survey compiled by Cesare Salmaggi and Alfredo Pallavisini with 620 illustrations and 84 maps—and B. H. Liddell Hart’s History of the Second World War, which has good maps but no photographs.

Keegan begins by quoting A.J.P. Taylor: “The First [World] War explains the second and, in fact, caused it.” That this claim is widely accepted does not detract from its important place in Keegan’s considerations on causes and ways the causes operated.

In Europe, the role of déjà vu was not insignificant. Keegan identifies the psychological effects of the Great War on events of 1940 and on Hitler’s thinking; he evokes the French defeat of 1870 and treats “the 1812 factor.” Hitler demanded that the armistice of June 1940 be signed in the railway carriage in which the German delegates had signed the armistice of November 1918. He quotes an American war correspondent concerning the Allied armies in Belgium: “It was almost as if they were retracing steps taken in a dream.”

—Catharine Savage Brosman

Although I have long known the author of this insightful study of the American conservative movement, which extends from the mid-1950s down to the late 1970s, I only recently got around to reading his work, thanks to a second-hand copy ordered from Amazon, which came with lots of passages underlined in red.

The author, Craig Schiller, who later identified as Mayer Schiller, is a Hasidic rabbi and teacher of Talmudic texts. In this 1978 book, he examines in depth the early conservative movement’s slide toward the left. There is nothing that Schiller describes that would not apply exponentially to where the conservative establishment has since gone.

Significantly, he places most of the blame on the “true believers,” the “party loyalists” who, “despite their increasingly vague programs have sought to shut out of their ranks any and all dissidents who fail to toe their line.” Please note that Schiller observed this censure before the rise of “conservative talk radio” and before the dreary drawing of party lines now promoted by Republican mass media. Those who dutifully recite what authorized “conservatives” encourage them to repeat may be, according to Schiller, an even bigger problem than faltering or opportunistic leadership at the top of the conservative movement. Although some of Schiller’s reform proposals now seem dated—for example, his plans to turn higher education away from the far left (as that term was understood in 1978)—his political suggestions nonetheless seem remarkably prescient. His call for the abandonment of the “faceless conservatism” associated with National Review and for an end to the rote recitation of free market slogans will resonate with those on the Old Right.

We may also welcome Schiller’s invocation of a pro-working-class right led by someone who could reach out to “West Virginian miners,” and “Pittsburgh steelworkers.” This hypothetical leader would also embrace “traditional morality” and avoid the temptation that Catholic philosopher Thomas Molnar described as “having their hearts half on the other side.”

Schiller’s now mostly-forgotten classic appeals powerfully to the vision of a populist right.

—Paul Gottfried

Leave a Reply