The GOP launched a seemingly coordinated campaign to celebrate Kwanzaa this year. “Wishing you a happy and prosperous Kwanza!” tweeted the official account of the College Republicans. It was a theme echoed by numerous other official GOP channels. In wishing his followers a happy Kwanzaa from the balmy state of Florida, Republican Rep. Byron Donalds was simply following in the footsteps of former Republican presidents George W. Bush and Donald Trump.

Donalds recently appeared on “Meet the Press” to debate defenders of antiwhite historical narratives, known altogether as Critical Race Theory. But the acceptance of Kwanzaa shows that Republicans either do not understand what they claim to oppose or do not actually oppose it. In many cases they have long ago internalized the myths that underpin antiwhite narratives.

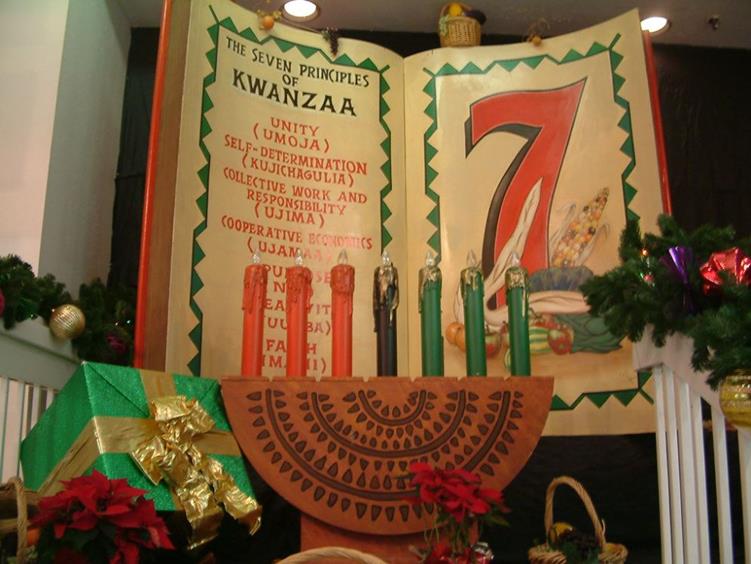

Kwanzaa originated as an explicitly anti-white, anti-Christian holiday. “A seven-day festival beginning on December 26th, Kwanzaa, created in 1966, is one of the most lasting innovations of United States black nationalism of the 1960s,” admiring historian Elizabeth Pleck writes in the Journal of American Ethnic History. Her article, “Kwanzaa: The Making of a Black Nationalist Tradition, 1966-1990,” provides an overview of Kwanzaa’s significance to black nationalists and race hustlers. “Kwanzaa was not merely a new nationalist ritual but an alternative to the dominant one of the season,” she writes. “Black nationalists were United States citizens assigning their national identity a far lower priority than their racial identity.”

Pleck includes a biography and quotes from Maulana Karenga, the holiday’s colorful founder. “Christianity is a white religion,” Karenga said. “It has a white God, and any ‘Negro’ who believesin (sic) it is a sick ‘Negro.’ How can you pray to a white man? If you believe in him, no wonder you catch so much hell.’” Considering that Karenga described Jesus as “psychotic,” it’s little wonder why Kwanzaa was intended to cancel Christmas.

Pleck chose 1990 as an “artificial end point,” marking Kwanzaa’s “refurbishing through consumerism” into a less overtly oppositional ritual. Acknowledging Kwanzaa’s antiwhiteness, Pleck cites journalist Anna Wilde, who concluded in a 1995 article for Public Interest, “Kwanzaa is essentially an effort on the part of African Americans to create community cohesiveness, though still unfortunately coupled in some ways with anti-white feeling.” Similarly, Pleck also notes that cultural critic Gerald Early once wrote in Harper’s Magazine that Kwanzaa “capitaliz[ed] on black hostility toward the whiteness and the commercialism of Christmas.” Kwanzaa’s antiwhite character is unsurprising, given the background of its founder.

Karenga was a black nationalist well before the Los Angeles Watts riots in 1965. But that event, like violence in general, was central to the formation of Kwanzaa. One month after the flames in L.A. flickered out, Karenga formed US, a black nationalist organization that, according to Karenga’s various answers, sought to effect either cultural or violent revolution in America. Kwanzaa is steeped in the Swahili language because Karenga believed parallel black institutions and culture were necessary for the formation of what would essentially be a nation within the nation. Swahili offered an alternative “national language” to English, the white man’s tongue.

Karenga’s personal life was fraught with tensions and conflict. Some divisions emerged between Karenga and the Black Panthers, who mocked him and his followers as “sissies and acid heads in yellow sun glasses and African robes.” The Panthers suspected Karenga of being an undercover federal asset, which was close to the truth. “The FBI’s efforts under its counterintelligence program, COINTELPRO, between 1969 and 1971 served to exacerbate Panther US rivalry and to curtail the sporadic efforts of nationalist leaders to effect a truce between the two warring organizations,” writes Pleck.

But the government didn’t have to work too hard to stir the pot. US and the Panthers recruited from rival youth gangs, making the violence in January of 1969 an inevitability. Four members of Karenga’s organization murdered two Black Panthers in a UCLA parking lot. The killings happened during a dispute between the two groups over the power to choose the administrators for UCLA’s nascent black studies program.

Karenga was no stranger to violence. He went to prison in 1971 for torturing two female members of US. He held them in a garage, beat them, burned them with cigarettes, and inserted a hot soldering iron into the mouth of one woman. Karenga’s first wife testified that he had sat on one victim’s stomach while pumping water into her mouth with a hose.

Black writers and intellectuals eventually rehabilitated Kwanzaa’s reputation, retaining its black nationalism while muting Karenga’s sordid legacy. Though the holiday has its roots in militant anti-capitalism, it was ironically the black middle class that helped mainstream the holiday. Kwanzaa was “The New Soul Christmas,” as one 1983 headline in the black monthly magazine Ebony put it. Despite what “colorblind” Republicans from Bush to Trump insist, Kwanzaa “became more widespread because it served the important function of affirming racial and familial identity within the black middle class,” as Pleck observes.

The widespread acceptance of Kwanzaa today shows that black nationalism has become mainstream. The Republican Party doesn’t even recognize Kwanzaa’s roots in racial militancy as an issue, and is happy to accommodate its demands not only by celebrating its festivals but by deconstructing the holidays and symbols of America’s European-descended whites. For example, last year Republican Sens. James Lankford of Oklahoma and Ron Johnson of Wisconsin proposed to replace the federal observance of Columbus Day with Juneteenth, the black nationalist’s alternative to Independence Day.

Even as Republicans fall over themselves to accommodate the racial grievances and demands of nonwhites and their white liberal allies, they clutch their pearls at the idea that white Americans can and should have their own culture, aspirations, and interests. This double standard shows that the GOP cannot “fight” Critical Race Theory, let alone see beyond its horizon, because its entire worldview is informed and defined by the very thing it claims to oppose.

Flickr-soulchristmas, CC BY 2.0