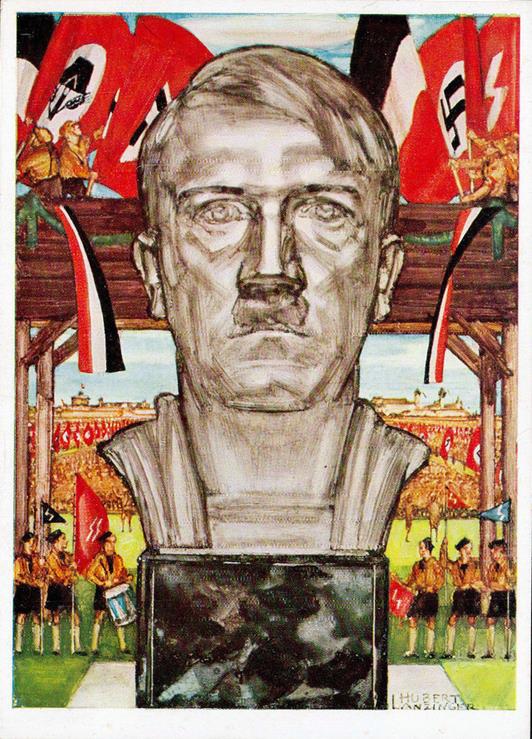

Today marks the 133rd anniversary of the birth of Adolf Hitler, and this year also coincides with the English-language publication of Hitler’s National Socialism, by Rainer Zitelmann, a distinguished German historian and free market economist. Reprising material from his German scholarship of more than 30 years ago, Zitelmann presents his provocative, well-founded interpretation of the Nazi leader as a revolutionary who set out in his own way to “modernize” Germany.

Zitelmann shows that Hitler was deeply impressed by the Soviet model of economic collectivism, even while rejecting Communist “internationalism.” Zitelmann’s cardinal points find an echo of influence in John Lukacs’s The Hitler of History, a work that is better known to Anglophone readers.

One thing is clear: 133 years after his birth in the Upper Austrian town of Braunau am Inn, Adolf Hitler continues to haunt and fascinate. From the issue of his ancestry to that of his mortal remains, the mania is not abating: the Führer remains our disquieting contemporary. This phenomenon arguably has more to do with the state of our present civilization than with his record, as the morbidities and neuroses of his century continue to follow us into ours.

Back in the early 1980s, the German historian Martin Broszat urged his colleagues to proceed from the demonization to the historicization of Hitler, to treat him as a historical figure and thus to determine his place in history. A few had tried even before Broszat’s call. Ernst Deuerlein’s concise Hitler: A Political Biography (1969) focuses on the question of “how Hitler had been possible.” Sebastian Haffner (The Meaning of Hitler, 1978) was also vexed by the incontestable unity between Hitler and the German people in the 1930s. Hitler reveled in that unity and agreed with Goebbels when the latter declared in 1938 that “a true democracy reigns” in Germany.

Lukac’s The Hitler of History (1997) made further progress. In its opening pages, Lukacs noted that popular interest in Hitler was prevalent on many levels,“from the honest curiosity of amateurs of history to the kind of prurient or near-prurient curiosity evinced by people who are attracted to manifestations and incarnations of evil.” To these, he went on, may be added the interest of those who wonder whether Hitler and Nazism “did not represent, mutatis mutandis, an alternative not only healthier than communism but healthier than the decaying liberal democracy of the West.”

Lukacs saw Hitler as the refutation of the view that history is made not by men but by underlying social conditions and economic forces. Far from being mad, Lukacs argued, Hitler was “a normal human being.” His evil intentions, notably the killing of Jews, “were spiritual, not physical,” which aggravates the crime. He also “may have been the most popular revolutionary leader in the history of the modern world … [who] belongs to the democratic, not the aristocratic, age of history.”

Given his acceptance of Hitler as a revolutionary in his ideas and rhetoric, in his plans and their execution, it is startling that Lukacs dismissed the view that Bolshevik brutality had affected Europe profoundly and provided an impetus for later Nazi outrages. The horror of Lenin’s and Stalin’s Russia is a key element in the totality of Western experience in the 20th century. Those tyrannies reflected the decline of the religious impulse among educated Europeans, which created a void that was filled with ideologies uninhibited by moral restraints and driven by the raw will to power.

Hitler was, as Lukacs dubbed him, “an idealist determinist” who asserted the ultimate import of will and the power of ideas. The Weimar Zeitgeist helped Hitler’s rise, but the very fact of his taking power allowed Hitler to create his own Zeitgeist. By endeavoring to overcome that to which he was bound, Hitler may have demonstrated that what men do to ideas is more important than what ideas do to men.

Perhaps the peculiarly German fixation on the bond between the word and the world is at the heart of the Hitler phenomenon. In Thomas Mann’s The Holy Sinner, the church bells of Rome are ringing, but there are no people. Who is ringing the bells? “The spirit of storytelling,” Mann responds. They are real bells, because once we have read about them, they do become real: they have been brought into existence as a conceptual province of reality.

In this strain of the German tradition, the world exists in the realm of ideas. Thus Field Marshal Kesselring argued—as late as March 1945!—that Germany’s ultimate victory could be predicted with “mathematical precision”: since defeat was impossible, victory was inevitable. “Smiling Albert” and his sort would not allow mere facts of a lower order to get in the way of their nominalist reality. This psychotic paradigm seems to hold the clue to a problem that remains unresolved: the malaise of Weimar politics and society notwithstanding, how could the generals remain so supine until so late in the day?

After July 1940, and acutely after December 1941, Hitler was strategically bankrupt. “His underestimation of enemy potentialities, always his shortcoming, is now assuming grotesque forms,” noted General Halder. When at last Stauffenberg and the rest steeled themselves to kill Hitler, theirs was a pragmatic rebellion against nominalist determinism, not a strictly moral choice. They felt responsible for Germany’s fate, not necessarily for its actions as such.

The lesson of Hitler is that the pursuit of global power for its own sake is the Great Temptation in human history, the path of ruin that winds from Xerxes to Napoleon to our own time. This lesson is yet to be absorbed by the Beltway regime which deludes itself to think that “the West has won” yet again, like in 1989, just because Russia might be bogged down in Ukraine.

Hitler remains our contemporary. He is alive because the American Democrat-Republican duopoly needs him. When its luminaries want to bomb a faraway nation, it is obligatory to hitlerize its leader (and, in the same spirit, to reproach the failure to go to war as a new Munich Agreement). At home, when they demonize opponents of nation replacement, critical race theory, or transgenderism, they compare those critics to Hitler.

Over 75 years after the reductio ad Hitlerum was defined by Leo Strauss, the practice is more widespread than ever. Its final corollary is that we are all potential Hitlers, and only by vigilantly guarding against deviant thoughts (e.g. “I like Texans better than Afghans”), discriminatory preferences (“I prefer straight women to lesbians”), intolerable tastes (“I’d rather go see the Ring than Fiddler on the Roof”), and microaggressive habits (“I am fond of taking my rottweiler Heidi for long walks”) can we hope to protect ourselves from the allure of the inner Adolf.

Pressing forward towards normalization of Hitler’s person and legacy is both possible and necessary. It need not and should not end up either in trivializing his record or in succumbing to the facile clichés about man’s capacity for evil. A wall may always separate us from Hitler, but the endeavor to see and understand is justifiable. This cannot be done, however, for as long as he remains an active participant in our affairs, largely thanks to those ultrasensitive souls who vigilantly detect him in everyone who dares disagree with their particular social, political, and cultural values.

Leave a Reply