There are two sorts of men in the United States: those who follow sports and those who do not. If you do not, you probably do not know that the Chicago Sky—yes, that is their name—recently won a national championship. If you do follow sports you also don’t know the news about the Chicago Sky, and you’d probably have to guess the sport: “Arena football? Soccer? Lacrosse?” And then it would dawn on you. “Oh. The WNBA.”

Apparently the people of Chicago didn’t know about the Chicago Sky either, or they didn’t care. The team’s open-bus parade down the main thoroughfares of the city, flanked with police on motorcycles, was rather sad to watch. Empty street after empty street; and finally a few thousand fans at the end, according to reports. Not a good show, in the sports-addled United States. Consider that every Saturday in the fall, from 60,000 to 100,000 fans throng the stadiums of every major college football team’s home games, braving all-day traffic and often bad weather.

Some commentators grouch about “prejudice” against the WNBA, but most sports writers—by no means conservative as a group—admit that, well, maybe it has to do with the quality of play. Oh, very possibly! The first time I watched a woman’s college basketball game, I was dumbfounded. I couldn’t believe it was so poor, so earthbound, so clumsy, and so severely limited in the athletic ability of the women players. “That’s a jump shot?” I said, as I saw a girl heave the ball from the level of her chest. I didn’t know at the time that the girls were using a ball slightly smaller than the one the boys and men use, to conform to their smaller hands. Imagine if they used the larger ball. Every close basket rims out.

Even in the land sport that rewards strength the least and that exacts the most severe penalty on the heavier male body—running—the best high school boys in the United States outperform the best women in the world, every year. In sports that do reward strength, forget it. There are probably hundreds of high school boys’ basketball teams that would bring the Chicago Sky down to earth and tread it into the ground. There are, I’ll bet, plenty of them in Chicago itself.

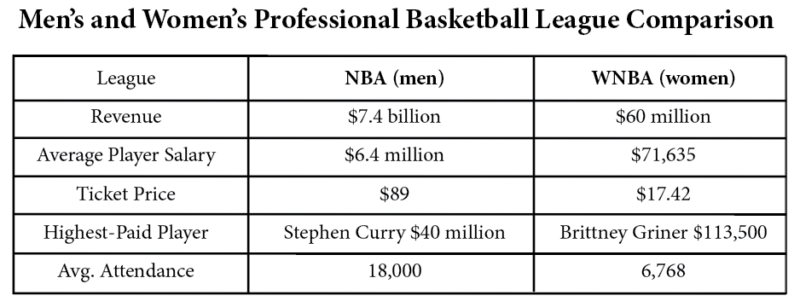

To be blunt, the WNBA is not a going concern. It is financed by the NBA, and it has averaged more than $10 million dollars of losses every year since its inception in 1997. The WNBA’s 12 teams have a regular season of a mere 32 games. That means a total of 192 games for the entire league, not counting a few playoff games (17 this season). The 30 NBA teams play 82 games each, for a league total of 1,230, not counting the playoffs (85 games in 2020). Attendance at WNBA games was down even before COVID hit. If we do the arithmetic, we see that the WNBA loses more than $50,000 per game. That’s chump change for the NBA.

chart: data reflects the pre-pandemic 2018-2019 season (source: www.wsn.com/nba/nba-vs-wnba/)

I can think of plenty of worse ways the NBA can spend its money. I can think of plenty of better ways, too. How about a matching fund, whereby the NBA will contribute dollar-for-WNBA-dollar to some private inner city high school for boys, most of whom come from fatherless homes?

If women want to play basketball for casual recreation, fine! Far be it from me to tell people that they can’t have fun on the court, ball field, or golf course. But when things become political, it’s another matter. Likewise when you slap a bill on my household for something I do not want and something I do not believe contributes appreciably to the common good.

To be clear, I am saying that women’s professional basketball—and women’s professional sports in general— definitely does not contribute to the common good. The real expense of it comes long before the WNBA with the expense for girls and women at the more than 100,000 schools and colleges in the country. This cost is borne by the taxpayer and by the families of college students. Suppose we said that colleges should only finance those sports that are financially self-sufficient, or those that help to forge a strong bond between the school and the community, which cost relatively little, and exact no unreasonable burden on the rest of the students. A few female sports would make the cut, and that’s fine with me. Male sports, on the other hand, would flourish. Many more men than women want to play sports to begin with, even if it means self-coaching, self-organization, self-financing, and no scholarships.

On what grounds could anyone call such a policy unjust? Men and women would equally be judged by reasonable criteria. Indeed, it would be more than just. It would be chivalrous, since the only way a women’s team can exist at all is by excluding men from competition.

The same would be true of boys and girls in our schools. If the interest is there, and you can fund the sport without much expense, go for it. If not, forget it. Again, the WNBA loses more than $10 million a year, which is a drop in the ocean compared with the money spent every year upon distaff basketball in our schools and colleges. Surely then we have the right to ask, “What’s it for? What do we get from it, and what does it cost us?”

The costs of women’s sports are not limited to money. At Providence College, where I taught for 27 years, Title IX inequities cost the school a popular male baseball team while setting aside a new softball field for the near-private use of a handful of women. On which, to no great interest of anybody, the women play a cramped sort of baseball derivative in an area smaller than what the Little League boys use at Williamsport.

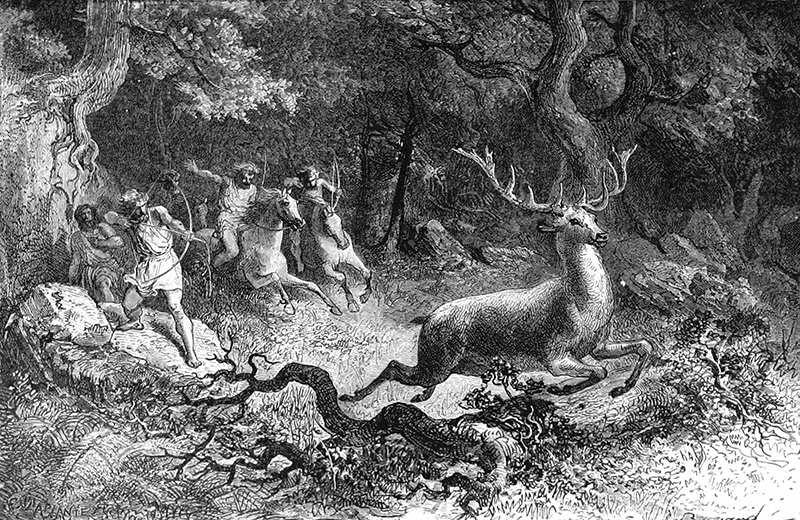

We know why boys and men play team sports. It is because boys and men fight, in teams. Without such teams, forget about civilization; human survival itself would not have been possible. The hunting party is a male team. The defenders of the village are a male team. The farmers clearing a field together, the road crew throwing a bridge across a river, the fishermen on a schooner off the Grand Banks, the miners hundreds of feet below the earth are all male teams—as were the senators in ancient Rome, and the teachers and students at the University of Paris in the days of Thomas Aquinas.

above: Bronze Age hunting team pursues a buck (Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo)

We have made a wager against nature. It is that we can have the benefit of the male team without having any male teams left at all outside of sports, while we put the screws to male sports in the meantime. Hence the female sports team, a copycat, is meant to prepare women to take part in what were once society’s male teams that contributed so much to the common good.

I understand the reasoning. I am not going to say that there should only be male teams. But not one fundamental social or public institution in our time remains healthy—not marriage, not the family, not the local school, not the churches, not colleges, not the arts, not newspapers, not the publishing houses. So I wonder, again, why we do not reconsider our command to boys and men, “Ye shall not make up a team unless we tell you so.”

In the meantime, what has happened to all the work that women used to do? I do not mean only the work that makes a home out of a house: the truly central work, for the life that all the male armies and senates are meant to subserve. Women have always and everywhere been the lifeblood of daily sociality. People who say that women used to be confined to the kitchen have very little notion of what went into making up a neighborhood. Who saw to your children when you had to go to the market? Who helped take care of the elderly or the ill? Who welcomed the newcomers to the street? Whose were the eyes that made it impossible for bad men to do things unseen?

above left: The Child’s Bath, oil on canvas by Mary Cassatt, 1893 (The Art Institute of Chicago/public domain)

For there is something else to say about those empty streets in Chicago. It is that they are empty also in Peoria and Rockford, Illinois, and in Warner, New Hampshire, where I live, and in pretty much every city, town, and village in the nation. Had it been 1950, those same Chicago streets would have been alive with human action, including swarms of children with the freedom and the security of a world in which men and women each knew what they were, and where their prime duties lay.

above: Minnesota Lynx’s Maya Moore, left, drives against Indiana Fever’s Jazmon Gwathmey during the first half of a WNBA basketball game in Indianapolis on August 30, 2017. (Darron Cummings/AP)